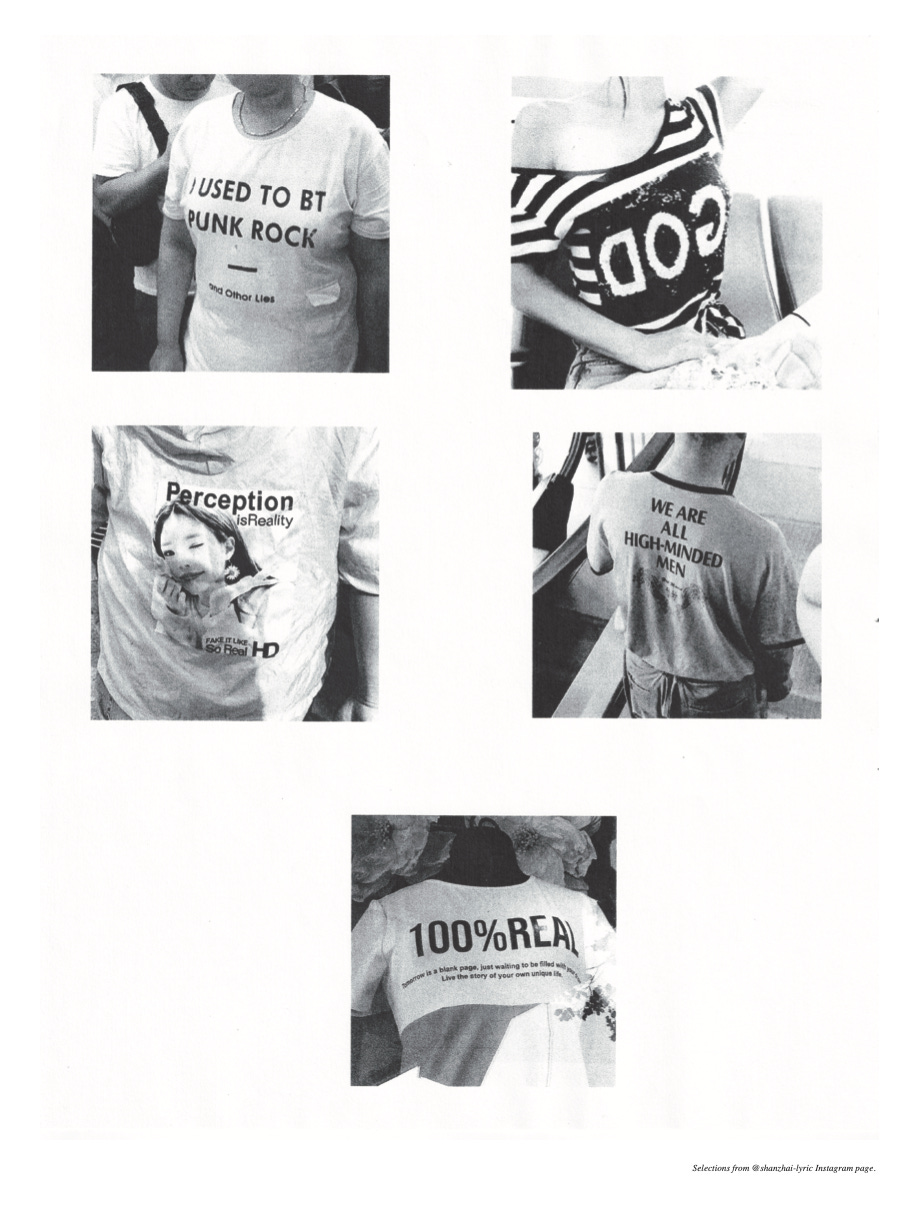

It’s tricky to define what the Shanzhai Lyric project is. A glance at the SL Instagram page reveals hundreds of text- based T-shirt designs, composed mostly in awkward or “broken” English. (See previous pages.) The text itself varies from inspirational slogans to approximated brand logos, to nonsense. The group’s name itself is taken from the “shanzhai” phenomenon, a trend of bootleg clothing and ephemera, one that SL collects and celebrates across dis-ciplines like fashion, art, poetry, and academia. Like Bur- roughs’ cut-up technique, these lyrics offer a way of divining new meanings from common language.

In Fall of 2020 a series called On Canal invited SL to occupy the storefront space at 327 Canal Street in Manhattan, providing a temporary home and area of focus for the shape- shifting project.

While the On Canal series itself appears to be a dubious corporate art/branding campaign, SL evades the pitfalls of retail beautification or influencer narcissism. Instead, the space under SL’s direction is something like a living organism, an evolving center of conversational history.

To passerby it’s unclear what, if anything, is happening in- side the Canal Street storefront, which is situated around the corner from the upscale shops of SoHo. The place is ambiguous in a way that inspires curiosity, and participation.

Anyone wandering by is likely to become absorbed into its ecosystem. Nearby street vendors pass in and out, locals scribble neighborhood memories on the walls, a guy from the clock store next-door wanders in one day and becomes a regular. He can often be found painting quietly in the back.

One can explore the archive by following its peculiar web of meaning. Thematic threads--themes of property, history, collectivity, language, lead from a storefront display to a note on the wall to a sole framed photograph in the far corner, to a repurposed piece of wood in the back room. The objects--found, painted, borrowed, or stolen, are in a suspend- ed state of play with one another. Games of synchronicity, pun, coincidence, approximation. Puzzling, sometimes un- comfortable juxtapositions. Translations of copies, of imitations, of copies. The visitor stumbles into a quantum game of telephone, disguised as a store.

SL isn’t curating so much as providing the right conditions, the proper pH for these threads to proliferate. One could spend hours in here, following the lines of collective memory, some old, some not yet created.

I visited the Canal Street Research Association in January of 2021 for a tour and an interview.

(Note: SL opted to answer questions as a unit, rather than individually.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Discussed: Threads, shine, bootlegs, Hamlet, landlords, cinema, appropriation, curators, curb appeal.

SL: Our collaboration began in 2015. We were given the opportunity to go to Beijing and research the phenomenon of what we call ‘Shanzhai Lyric,’ which is the beautiful poetic nonstandard English you often find on fast fashion shirts coming out of South China, and worn kind of everywhere. We used that occasion to visit this multi-level women’s clothing market and start thinking about and spending time with these phrases. We were really excited, because we’d started thinking about translation and mistranslation, and effects of global restructuring and distribution, these networks. So yeah, we were excited to dive into the heart of these kinds of exchanges, and actually feel the synthetic materials that were there. At that time we didn’t have any money, so we couldn’t actually physically acquire any poetry garments. But over the years there were various opportunities where we had the funds to start physically archiving them. This area over here [gestures to the left] is where we’re presenting this 150-200 piece collection that we’ve amassed so far.

The impossibility of purchasing these poems that we would see in space, either being sold or being worn through the city, has informed our thinking about ‘archive’ in the expanded field. Like, what is an archive of an object if you don’t have the object? How do you circle around it, writing about it, transcribing a memory of it, asking for somebody else’s memory, using other objects as gestures towards that thing that can’t be acquired? In a way it’s a restriction that has guided the practice.

A shanzhai t-shirt is a liminal object that’s both a garment to be worn and a document to be read. So, how do you categorize an object that confounds categorization? We archive them architecturally, making gathering spaces out of the textiles that could be spaces for translation experiments, conversation experiments. These structures are inspired by different shapes and frameworks: runways, scrolls, reading rooms, heaps, closets, stages, laundry lines, billboards.

We don’t typically have a place to store these that is publicly accessible; the project kind of follows the resources. It’s also part of our attempt to put the archive inside other archives or institutions or spaces or homes or collections. This residency at Canal Street Research Association is actually sort of a unique scenario, where we have a physically grounded space to call our own, temporarily, where we can offer an experience of the stuff.

What were your individual practices like before Shanzhai Lyric started?

Ming was, and still is, primarily an editor for various arts, design, and architecture publications. Living in Hong Kong at the start of the project, she was already closer to the phenomenon in one sense. Her background is in anthropology and art history. She had been witnessing these phrases in the market, and at small pop-up shops that sell surplus all around Hong Kong. One particular focus of hers was in these kinds of itinerant architectures that emerged in the place that has a very close relationship with where the majority of goods in the world are made. Hong Kong acts as a sort of processor of both products and raw materials. It’s always this interface between the consumer and the producer, and East and West.

Alex is primarily a clown, thinking about embodiment of language. Language in a sculptural sense. And also the insights of what we might consider to be nonsense language, research on multilingual poetics. Like, how do you translate a text that is in many languages at once, including what appears to be nonsense? And how does nonsense actually open up many more possibilities of interpretation, rather than limiting?

So, in a weird way, we discovered each other’s research anew, and felt these synchronicities which came together in this shared excitement around the Shanzhai Lyric as a potentially liberatory idiom that offers very fractured insight into the experience of living in global hypercapitalism. And is traversing the world on bodies. So there’s also this excitement around the text itself being curved and bent. Because it’s meant to be worn, and it’s meant to fall apart and disintegrate, and appear in these really fleeting ways, which is something we’re thinking about recently, in terms of collisions of different timeframes. The process of archiving is one that has a particular pace that goes against the way fast fashion functions in the world.

While in Beijing we got really excited thinking of the politics of ‘shine.’ Shininess is a quality that both attracts and obscures something—perhaps unseemly—beneath. Shanzhai Lyrics are really sparkly, really shiny, but they also belie this degradation of quality that is the result of different shifts in production and labor practices. And also, the shininess refracts. It draws your attention, then it refracts it, or reflects something new and mutates it. So yeah, that was sort of the foundation of the project and then somehow it just ended up going on and on.

There are always more ways to continue following threads. This particular instantiation at Canal Street was really the result of happenstance. We had been fundraising and scheming how to continue the research in a really global way, to trace the pathway of certain counterfeit garments and speak to people that work with the materials at their inception.

We were very interested, for instance, in the Museum of Counterfeit, in Paris. We were planning to insert ourselves non-officially as researchers in residence there. [laughs] The museum is really fascinating. It’s a very charming museum that will show you a Chanel glove next to a bootleg Chanel glove, or whatever. But its actual purpose is to train border guards to be able to tell real from fake, in order to control what’s coming into the country. It’s a relic from the Prussian empire. So it really crystallizes for us how thinking about secondary markets and counterfeit goods is also a way of thinking about the arbitrariness and artifice, but also very real world implications and violence, of borders. The museum is owned by LVMH at this point in time, but it’s still used for training.

But it’s publicly accessible?

It’s seemingly been absorbed into LVMH, which is obviously a much larger scale enterprise. It’s in this Art Deco building with a carving that reads ‘The Union of Manufacturers,’ and is pretty unattended. We’ve been there one time, but suspect there’s a more updated portion of it behind the public access point. But yeah, we’re really interested in investigating the origins of language used to legitimate property, and thinking about how the definitions used to determine the official and non-official come into play in the violent maintenance of borders.

When travel became impossible, and because of those same circumstances, a lot of space was left vacant and became available in Manhattan—people couldn’t rent their property. We were able to bring the same concerns that we had been theorizing and planning to trace in other places to the microcosm of this block: Canal Street. We’ve been able to realize the extent to which research at the level of the very local is perhaps richer. We both grew up right nearby. And the global trade routes and dynamics that we were already interested in researching come to a fore right here.

When all of these storefronts on Broadway were boarded up by landlords in fear of looting during the uprising, it really illustrated the different mechanisms that go into the maintenance of property and the language around who gets defined as a theft, when there’s obviously a much larger theft by landowners and corporations responsible for the dispossession and expulsion of people, as well as by the police who regularly raid, or you could easily say steal, the possessions of street vendors. The police and those whose class interests they protect are the true looters of small, local businesses.

So this is the first physical home the project has had? The first space of your own?

The archive has lived in different exhibitions, homes, and institutions more temporarily.

A lot of the archive is digital, right? Photographs of what you find?

We have @shanzhai_lyric on Instagram, which is one of the first iterations of the archive. It was also a way to open up the archive to submissions. A lot of the poems on there are sent to us by Instagram users around the world. But yeah, I think the digital and physical archives complement one another. The interesting thing is, fast fashion is ubiquitous, and yet these are actually really precious items. The cycles are so rapid that if you see one it will so quickly be thrown in a landfill that you’ll never see it again. Shanzhai lyrics are at once ubiquitous and precious and rare. So documenting them feels really urgent.

Where do you source most of the physical articles from, when you have a budget?

These were mostly sourced in South China and Hong Kong. Some are from outdoor markets in other countries or right nearby.

The term ‘Shanzhai’ itself has a built-in connotation of redistribution. Do you think of Shanzhai Lyric as a political project? I’ve seen references to Marxism and stuff like that in descriptions of what you do, but I’m curious if those are ideas that guide you.

It certainly is a political project in that we are committed to de-hierarchizing language regimes that place so-called standard English at the top. We celebrate all interventions in the imperial dominance of English. We are also very inspired by the kind of seeming ideological underpinning held within the etymology of ‘Shanzhai,’ which means ‘mountain hamlet,’ because of the liberatory potential that it implies. The term allegedly comes from the Song Dynasty legend of the water margin, which is a Robin Hood-esque story of scholar-recluses absconding with resources from the empire and retreating into mountains to redistribute the wealth among the people. We found that to be a very rich definition to draw from, and we continue to draw from it. We consider Canal Street to be hamlet in many ways.

The lyrics offer a different way of thinking about authorship and ownership that allows for consideration of value as something that accrues from collective collaboration and co-creation rather than this false attribution to and valorization of a single individual.

[A vendor from across the street walks in and greets Ming and Alex. This is Khadim, a bag salesman on the block. ]

For us it’s a way of thinking about a different approach to ownership and property, so in that sense it’s certainly a Marxist project in its grounding. But I also think we appreciate the role of ‘researcher,’ insofar as we can’t claim to be doing anything other than research. What we’re interested in is having conversations, and thinking about why it is that people are so excited to talk about these things. A great source of energy and hope in a way.

[Khadim reappears with two djembes and exchanges goodbyes as he leaves the room.]

These particular objects or phrases as a starting point for a discussion of the possibility of another way of thinking about property brings us delight and joy. The way in which it’s a political project is related to the way in which it’s a poetic project: to see how a different language for conceiving of property and theft opens up a different way of relating to one another, and how we could restructure our relationships to our homes and communities, our ways of describing and inhabiting our environments.

Do you ever worry about removing stuff from the vernacular by archiving it? By taking it out of a more utilitarian setting?

Do you mean appropriating?

Not necessarily, no.

It’s important to us that the archive is always shifting its form and context. I think we would have that worry if we were removing things from the cityscape, let’s say, and placing them into an institutional box. But that’s sort of why we seek out a ridiculous variety of contexts. We want the canon makers of arts and poetry to be aware of this incredible avant grade work being made in a context they might not be in contact with. At the same time, we are equally, if not more excited for it to be in a place that any passerby on the street feels sort of welcomed to engage with and touch and wear and rearrange. So we would have that worry more if it was moving only one direction.

We’d be wary of it seeming like we’re relying on the validation of one particular discourse or institution. We’re maximalists for the purposes of diversifying the range in which these can be legible, or encountered as an invitation into the illegible.

So that it’s not functioning only in an academic setting, for instance?

It has functioned as that, it has functioned in an art context, it’s functioned in the context of a feminist library, or a de-colonial archive, or a community center, or stranger’s personal closet. It’s a project of circulation that we want to be constantly circulating.

Maybe that touches on another question I had, sort of about straddling these different worlds. Art, poetry, fashion, research, theory—does one of those categories feel more like home to you? Or is it important to have a foot in each?

We ironically feel most alien to fashion, even though the material substance of this research is clothes. Initially we were very committed to the physicality of the language. The idea of poetic research is sort of the root. But the in-between-ness and ambiguity are definitely more important than any particular arena, which the space here has really brought to the fore. It’s quite uncomfortable in a way for us to be in an arts context, although we try to be as parasitical as possible in terms of getting whatever resources we can that makes further travel and conversations possible. But what’s important to us is that it isn’t clear what it is, and that is what makes people curious, and that’s what makes people want to come in and talk to us.

We take a lot of cues from the lyrics themselves, essentially. Like, if the space appears nonsensical or ambivalent or fragmented, it’s because we’ve taken a lot of tactics from Shanzhai lyrics and their ‘in-between-ness.’ A bit shoddy, and a bit shiny, [laughs] and somewhere in between an artistic endeavor and office space and...

Like you were saying [before recording], it’s unclear whether things can be purchased or not, which is the key confusion here. People enter because they want to know if there is something to be acquired and if they can acquire it. And when it becomes clear that there isn’t, the conversation often shifts to them wanting to collaborate in some way, to bring in their wares or art or ideas, memories, stories, which is really quite striking. Somehow the confusion opens up the possibility of collaboration and, therefore, collective authorship. Which is exactly the strategy that we thank the shirts for. [laughs] It’s more interesting to crack open the possibility of this co-writing together, of what the space is and isn’t.

It reveals a lot about desire, what constitutes desire, how desire is constructed. One thing we sort of observe is, consumption is based on the ideal, the dream of possession, which is never real- ized and therefore leaves us constantly in the lurch, in terms of leaving us fulfilled. But then with these phrases that are some- how broken, or nonsense, or seemingly errant in some way, we feel more seen or more fulfilled. Because they articulate this broken desire that we all walk around with, or something.

The lyrics more precisely describe the feeling of being alive in these circumstances. [laughs]

The vague nature of the space is particularly refreshing in New York. Or confusing. Things are so product-driven here. You walk around, and you can pretty quickly tell what’s being sold somewhere, what the bottom line is. To wander into an ambiguous space like this is sort of a special thing.

There’s a script. There’s a script we walk into a store with, which is that you’re a consumer and you have a choice. You can buy it or not buy it. In an art space there’s another script, which is you walk in and contemplate something you’ll probably never be able to acquire and feel slightly alienated by.

In some way maybe we’re slightly tricking people. They come in thinking they know how to operate or how to carry themselves, and then we’re like, ‘Tricked you, there’s nothing for sale.’ But then maybe they’re open to another kind of encounter. The store script is more accessible to more people, perhaps. This is our assumption, anyway. As opposed to the gallery script, where it can be unclear how one is supposed to be interacting with the space. Or a sense that there are protocols you might not be fluent in. The store is like, OK, everyone has to go to a store. We know how to do this. So we try to lure people in and then interrupt the script, basically.

Has there been a lot of engagement from people just walking in?

Oh yeah. We can’t get any work done! But engagement is the work. Yeah, it’s great. So many stories. It’s kind of incredible the people the space is a magnet for. Folks that are more old-timers notice immediately when something is out of wack. People who have lived here for 20, 30, 40, 50, sometimes 60 years, come and really study and try to figure out what’s going on. And then it’s a pause, and the pause is the moment that some kind of encounter can really have room to happen. We’re also really inspired by thinking about stuttering, and conceptual stuttering, and what that would be where there’s an interruption in the flow that allows for longer listening.

As for particular encounters, early on we had a film series here where we projected films on the window. We just shifted away from that phase because it got too cold out. In September, October, November we had a socially-distanced outdoor theater, and we would have the posters up [grabs posters] on the front window. There was one day—this is one of many miraculous synchronicities—we had a poster up of this kind of ridiculous pairing, Hamlet and the Rent- ed World paired with the 2014 remake of the musical Annie, which won an award for being the worst re- make ever. Annie was shot around the corner from here. [shows poster] We had this up in the window for a little while, and we saw this spectacular woman staring really closely. She had an incredible hat. We had to talk to her. It turned out that she lived around the corner, at 18 Mercer, where the fragments that became Hamlet and the Rented World were shot. Where Jack Smith was rehearsing his avant-garde Hamlet, which never quite got made because of the precarity of his real estate situation. We told her, ‘Oh you must know Jack Smith! That’s why you’re looking at the poster? That’s incredible. 18 Mercer, what an incredible address to be.’ And she was like, ‘Why? Because I live there?’ Well, yes, but also...It was a total coincidence.

The whole premise of Smith’s staging of Hamlet was his conviction that landlordism is the central evil of our time. And he was in the process of getting evicted from his artists’ loft. So he developed this obsession that at the heart of every play is the evils of landlordism being dealt with, processed. In his retelling of Hamlet the royal family are a family of landlords.

Right after he was evicted, Tracy moved in and has benefitted from certain loft laws.

We’ve been thinking about the legacy of artists in the neighborhood as authenticators of space that later get displaced. Part of something being authentic is being ‘an original.’ Being original is something that property developers try to replicate in order to elevate the value of the property that they own, which ends up being sort of an empty shell of that original thing.

[We flip through the posters together.]

So you’ve hosted drum classes in here?

Khadim [who walked through earlier] sells bags across the street, and we got to know him over the course of being here. He shared with us that he’s a griot, a musician and storyteller from Senegal. He came here pretty recently, a little over a year ago. He’s started teaching some kids on the block how to play African drums. He gave a drum lesson and performance outside as a kind of concluding celebration of our Window Cinema series.

[Flips to another poster.]

A thread of the research that we’ve become obsessed with is the Hamlet story, and different reinterpretations of Hamlet, which is itself a bootleg text, because Shakespeare essentially stole it from another author and collaged together many fragments of stories. Disney claimed The Lion King was their first “original” story, but many say it’s a version of Hamlet, but in fact it’s a really close bootleg of this Japanese animation Kimba the White Lion by Osamu Tezuka, which is itself a bootleg of the epic of Sundiata Keita, about the founding of the Malian Empire. So it’s a story that a lot of the vendors and artisans around here are very familiar with.

Another really weird resonance was that Khadim, who has toured the world as a musician, previously lived in Jeju Island in Korea, in an African museum that is a replica of the Grand Mosque of Djenne in Mali. So Khadim was living in a bootleg Grand Mosque in a small tourist island off of the Korean mainland. Essentially we’re just following all these associations of stolen texts. At the very inception of the whole project was our interest in Shanzhai lyrics. But being here we’re tracing Shanzhai writing into all these different settings. And also riffing off the double entendre of ‘Hamlet.’ (Shanzhai, of course, meaning ‘Mountain Hamlet.’)

I have to confess to not having seen Annie all the way through. So I’m not sure I know the Annie / Hamlet connection.

[They laugh, then direct me to a single framed photograph hanging by itself nearby.]

Do you recognize this at all?

No... Should I?

[laughs] Probably not. One day we went to go get some wood from the Chinatown Building Supply right around the corner, and there’s this wall of photos by the door. They seemed to be stock images, like gorgeous flower, gorgeous sunset. And then this one. So we were like, ‘Wow, what’s the story with this? Who took this photo?’ The woman there told us that the owner of the shop is also a photographer, and that he photographed this. We were like, ‘Oh my God, did he see someone almost get hit by a car?’ And she said, ‘No. Actually, they were filming the 2014 remake of the musical Annie right across the street.’ So he must’ve been watching them reenact this car scene over and over and over. That’s Jamie Foxx’s stunt double.

Wow.

And that’s Quvenzhané Wallis’ stunt double. This is like a pivotal scene in the movie. So this is the representation of a stunt double, in a remake. A bootleg of a bootleg of a bootleg. [Everyone laughs.]

So anyway, we had him sign it. (This is another thread/obsession of ours: how value accrues through the addition of insignias.) The artist’s name is Bon Lee. Now at the entrance to the wood shop, you’ll see a vacant spot on the wall where it was. There’s maybe 40 framed photos, with one missing.

The Window Screenings have been a mode of research for us, but also an invitation to the block. We wanted to screen things that were local happenings but also with more mainstream appeal Annie was an invitation to the block. Following Jack Smith’s hypothesis or offering that landlordism is at the heart of all narratives, we were interested in Annie because, in the original at least, Daddy Warbucks is this evil landlord figure. In the remake he’s a cell phone mogul.

Nice.

[Flips to another poster.]

The Bad Sleep Well is Kurosawa’s Hamlet, which we paired with Hollis Frampton’s Works and Days (the title is based on a text by Hesiod) that was composed of found footage from one of the junk shops that used to line Canal Street. He took the footage and simply applied his signature, his stamp to it. This intersects with the thread of insignias accruing to an image we’re kind of obsessed with as it relates to Chinese landscape painting. Byung-Chul Han, a scholar who writes about Shanzhai, describes it as continuing Eastern landscape painting traditions in which an image passes through the hands of many people who own it over time, and they each apply their own signature to it, often in the form of a poetic aphorism. So it acquires all this text around the central image and gains in value because of the many author-owners, in opposition to the more Western mythology that valorizes one genius author. As you own things you also author them.

[Flips to a new poster.]

This was a film shot in a basement nearby, where the artist Patty Chang reenacted the historical meeting of Brecht and the Peking opera star Mei Lanfang, which inspired Brecht’s theory of alienation. The film is based on a transcript of the meeting which was thought to be documentation but was later revealed to be a play. So, again, this slippage between real and fake. The ‘official’ text is also often imagined into being. The film was geographically relevant, but also we think a lot about alienation in terms of the effect that Shanzhai lyrics can elicit, whereby something familiar is made unfamiliar, and this estrangement can reveal something. And then we paired that with another sort of fantasy cultural encounter, Berry Gordy’s The Last Dragon. Have you seen it?

I don’t think so.

It’s really good. It’s about a young black man, Leroy Green , who’s so inspired by Bruce Lee that he changes his name to Bruce Leeroy. It’s really fantastic. He basically wanders around Chinatown in Chinese dress seeking out the Master who he thinks is writing these philosophical aphorisms, but it turns out to be a fortune cookie machine. More human-algorithmic poetic collaboration and trickster wisdom!

What era?

80s. It’s a total must see. Because of its exploration of mutual cultural fetishizing and appropriation, it somehow still holds up. It’s not something you’re watching like, ‘Wow, this is wildly inappropriate. How are they getting away with this?’ The film uses humor to talk about cultural appropriation in all of its complexity. This kind of desire and obsession with wanting to embody the other. And in doing so, creating a flawed copy, a questionable bootleg of the original that reveals something about longing. It’s really good.

‘Appropriation’ has become a dirty word. I get why, but it’s also a narrow framing, one that presupposes an idea of intellectual property--as opposed to a traditional folk approach to culture, for instance. Shanzhai lyrics, as a form, seem to subvert or play with this element by blurring lines around property, theft, borrowing, and sharing.

Well, the politics of appropriation have to do with im- balances of power and access. That’s why we (hopefully) embrace the tactic of reappropriation, rather than appropriation. A bootleg of a luxury brand is a form of reappropriation, using found text to make a statement, a critique, or a creative innovation. Corporations bootlegging bootlegs (which they now do, having realized the power of the street) is appropriation.

I was thinking of the lyrics themselves as offering an alternative by flaunting a lack of authenticity.

Defining cultural exchanges as strict exchanges of power is tricky. Viewed through that lens, couldn’t you two, as educated Americans or participants in worlds of art and academia, be implicated as the ones with power and access?

Absolutely we could.

Curators often function as gatekeepers of information. Do you think of yourselves as curators? Is there reason to be suspicious of the role of the curator in the more traditional sense?

We prefer to consider ourselves as archivists rather than curators. Perhaps this speaks to the liminal nature of the items that we are working with, insofar as they straddle multiple fields of discourse. This is a long term project in which we seek to take objects that are typically cycling through our lives rapidly and create a space to dwell on them and consider their longer term impact. The tension between the speed of so-called fast fashion items and the anachronism of archiving is, to us, a productive one.

[Flips poster.]

Our friend, the artist Jonathan Berger, has curated many amazing shows but prefers to refer to himself in that capacity as an ‘organizer’ rather than curator. This also resonates with us. We are organizing a lot of logistics. We are organizing happenings and facilitating encounters, rather than selecting or elevating certain objects or individuals over others. Other words we gravitate towards include importer or trader or courier. The art world often uses elevated language to distance itself from the nuts and bolts operations of being in the business, essentially, of luxury sales.

[Flips poster.]

We had to show the iconic Ethan Hawke Hamlet, and we paired that with a durational performance that the artist Yoko Inoue actually did right next-door, on the steps of Canal Rubber. She worked with artisans in Ecuador to import alpaca sweaters that were replicas, bootlegs you could say, of sweaters she had seen emerge on the market right after 9/11—patriotic alpaca wool sweaters knit, with American flags on them—and these knitted hats. She sat in a stall in front of Canal Rubber and slowly unraveled them to the bemusement of tourists. The funny thing is that when we were looking at the stills of the two films we realized both Yoko Inoue and Ethan Hawke were wearing those hats. The Ethan Hawke Hamlet came out in 2000. The hats were very of-the-moment it seems. One of those Canal Street trends. The documentation of her performance is really beautiful, because she’s returning the items to their raw material form, unspooling them into balls of red, white and blue. But then she works with artisans to weave them into new objects, like flowers, without the American flag. It’s a depiction of the Western empire unravelling.

[Flips to a new poster.]

We had to screen Ghost. A classic SoHo gentrification story also connected to the ghost in Hamlet, the theme of properties being haunted. And also a tale of a doomed romance between artists and developers... We’d love to resume the Window Series, but it’s just too cold right now.

It’s warmer today than I expected.

You’re lucky, because the heat is broken. It’s cold right now, but it’s usually really cold.

[We begin to look at the photographs, and scrawled accompanying text, lining the walls.]

These are all photos we took of every storefront on Canal from the East to the West, from the Hudson River to Essex Street. It’s to jog peoples’ minds of any personal memories or local lore. In the remain- ing time here we’ll keep inviting people to add to the timeline. It’s funny, because people walk around and they add stuff, and we don’t notice it. Occasionally we look around and we’re like, whoa. [laughs]

I had an experience with a friend over the summer, who was looking for some bootleg shoes. It was interesting, we had a guide taking us from station to station, checking with the different sellers. I hadn’t realized it was such an ecosystem.

Yeah, the perception is, ‘Oh, they’re all selling the same thing, so they must be in competition.’ But there’s actually a lot of camaraderie.

Yeah, it seemed like more of a network or something.

It used to be more Chinese vendors on the block, but since the 1980s or so there has been an increasingly West African presence. Many of these vendors come from countries like Senegal, Mali, Guineau Bissau, and the two demographics tend to express having a positive relationship with one another whereby the Chinese do the importing and warehousing, selling the goods wholesale to various vendors.

The location seems perfect for your project. People sell bootlegs outside, and you’re a short walk from galleries in one direction and upscale clothing stores in another.

It is really great. People remark on how odd it is that Canal Street has managed to elude a certain kind of gentrification development scheme. We often ruminate on why. It does have a bit of a throwback gritty feel because of the traffic and the energy of the two way street running from the entrance into the city through the tunnel. We always ask people what brought them to Canal when we talk to them, and one of our favorite passerby friends that we met was just like ‘the corruption.’

I guess that’s harder and harder to come by in this city. Seediness.

Visibly, yeah.

Right, yeah. Not actual corruption.

There’s lots of that.

[In the storefront window of the space are a pair of busts. Ming and Alex also point out traces of a previous installation on the windowpane itself.]

SL: On the windowpane, this is held over from our last window re-staging, which was by the artist Paige K. Bradley, where she restaged a show that she had installed further East on Canal right before lockdown, on the 2nd floor, which looks onto a historic bank building at Bowery and Canal. Below the space is a First Republic Bank, whose logo is an eagle—these are bootlegs of those eagles.

Is this glue residue?

I think it’s clear acrylic. We asked her to leave it up. It’s like a secret piece.

I think if I’d discovered this on my own I’d be losing my mind right now.

Well, it’s funny, one of the small conflicts we’ve had with the actual landlord here is that our displays aren’t polished enough. i.e. we are not partaking in the kind of upscaling or improvement of this store- front as they would intend for artists to do. It doesn’t look like art, essentially. The movie posters were all painted on the original paper that had been put up on the window when they were doing some renovation. We deliberately kept the painter’s tape on. They did not like that.

Because the place still looked closed or abandoned ?

Yeah, essentially. It didn’t look active, it didn’t look vibrant, or whatever they want the space to be. It didn’t look shiny enough, basically. They just told us that we weren’t professional, and that the only way we could justify using unprofessional materials was if it looked intentional. But what does it mean for something to look intentional? It’s honestly a very interesting question, and one that comes up a lot in relation to the Shanzhai lyrics. How do you deter- mine artistic intent? How do you determine whether apparent mistakes are intentional, an error or an aesthetic, poetic, political choice? You can’t, but you can be open to that possibility. Everything in here is, if anything, perhaps too intentional. But something like this [gestures to the eagle shapes] probably still would not meet their specifications for looking professional. And that’s intentional.

It seems like a lot of the imported Chinese goods around here tend toward fake brand names. Do you encounter many Shanzhai lyrics in Manhattan’s Chinatown?

It’s actually not that rare. It’s interesting, because the presence of Shanzhai lyrics does not seem to correlate to a level of English proficiency or something like that. I’ve been back to China several times since we started the project, and I’ve noticed that in North- ern regions like Beijing or Shanghai there’s a lot less Shanzhai lyrics around, whereas in Hong Kong there are still a great abundance. In Hong Kong, a former British colony, people learn English at a young age. Which seems to indicate that the phenomenon of Shanzhai lyrics does not correlate with a lack of English proficiency. Which is to say, it’s not a mistake. It’s an intentional flubbing of the rules. Or just a basic disregard for the rules.

Have you encountered ‘lyrical’ translations made or manufactured outside of China? If so, do you include them as part of the phenomenon?

We get a lot of submissions from countries in the former eastern bloc—a lot from Georgia—but these are possibly also manufactured in China. But it’s also possible that they have been designed and churned through different language processors. We have found amazing collections of Shanzhai in places with thriving Chinatowns, or sizable populations of Chinese diaspora, such as in Barcelona or Panama City. There are many Shanzhai lyrics from Vietnam, for instance. Vietnam also has a Canal Street connection, since many of the nonofficial markets here were instigated by importers involved with the black market of goods during the war. At any rate, we would consider them Shanzhai lyrics based on a sort of loose set of terms that include a seeming irreverence towards the norms and codes of English, as well as a sense of humor, subversive shininess, and a collision of linguistic registers. Then, of course, there is some blurring of the line—big retail chains like Zara increasingly make Shanzhai shanzhai, and it can be hard to tell if you are finding an ‘authentic’ bootleg or a replica. But this total collapse of distinction is kind of exciting.

Totally. You mentioned Hong Kong as a sort of physical embodiment of some of the polarities that Shanzhai brings up. It’s on the cusp between East and West, consumer and producer, etc. In recent years China seems to have become increasingly prominent in the American or Western consciousness. (I’m thinking of widely covered protest movements in Hong Kong, the CCP as a scapegoat for the coronavirus, etc.) Do you notice changes or trends in Shanzhai as things like that ebb and flow in the American media?

We tend to perceive Shanzhai lyrics as an acute cultural barometer. For example, there has already been a proliferation of Coronavirus-related prints (seen in some Canal Street shops), as well as a lot of recent garments around the time of the attempted coup at the Capitol bearing text related to the failing of government functioning and communications. These felt supremely relevant; in a sculptural, structural fashion, governmental discourse is indeed falling apart, the fabric of society coming apart.

If anything, it seems like the pace of absorption of events and ideas by the poet-producers of shirts is only metastasizing. Given that it is probable that a lot of the content is gathered and collaged from the web, this is in step with the hyperbole of social media and the speed by which content is churned out.

Will you have some sort of closing event to end the residency before you leave? Some sort of punctuation mark on your time here?

One of our aspirations is to make a film, but I can’t say that it would be done by the time we leave here. [laughs] I mean, yeah, it would really be great to have a celebration of some kind. However, if it’s at the end of February it might feel dismal. [laughs]

In a way, we don’t mind slipping away, because the project will continue in some form. We don’t feel a great desire for some punctuating event, more just to think about a way to honor or in some way hold space for a lot of these memories. It’s really important to us to bring as many people in here as possible and talk to them about what this brings up for them, and have that be imprinted on the space in some way before we leave. That’s the most important thing for us.

You’ve worked together as SL for years. Is there anything about the project that feels especially relevant now?

Being right here and having this opportunity was only possible because of the contestation over the value of real estate when people can’t go inside. It’s very present for us, being inside the paradox of that. We only have this space because people aren’t supposed to be going inside together . So there’s something kind of heartbreaking in that, because it feels really important for people to have a physical space to go and be together right now. And at the same time it’s also impossible. On Canal, we have a window, very literally, onto the corruption and injustice at the heart of the whole operation of capitalism. We have witnessed multiple questionable police raids on the street vendors, for instance. A lot of our research here looks at how street life itself has been criminalized and outlawed in a racist, anti-poor and anti-immigrant impulse dating from the 1800s. On stolen Lenape land. So the events that opened the opportunity for us to even be here at all are also intimately tangled up with the questions that we’re thinking through, in terms of the criminality of theft that is so central to the white supremacist project. So yeah, it feels al- most excruciatingly timely, because we’re witness to a lot of the violence inside all of that right here on this very block.

But yeah, unfortunately it doesn’t necessarily feel more timely than other times. [laughs] It felt urgent always.

__________________________________________